Paul Holmes 19 May 2014 // 12:37PM GMT

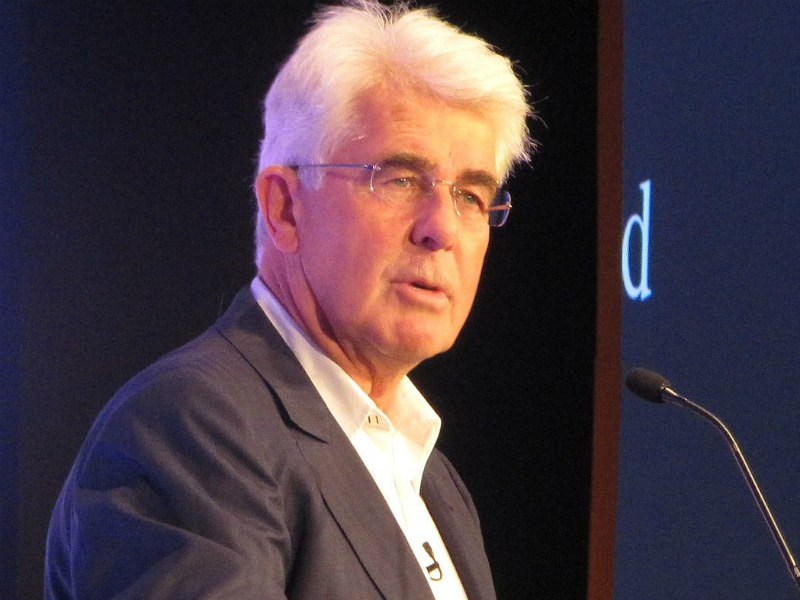

Is Max Clifford—convicted last week of indecent assault on several teenage girls—a public relations man? It’s a question that seems pertinent, given the commentary by Ian Burrell in The Independent and others suggested that Clifford’s conviction has “tarnished the image of PR.”

Burrell’s argument is not entirely specious. “If you’d walked down any High Street before this scandal broke and asked shoppers to identify a PR person, the silver-haired and silver-tongued Clifford would have been the most popular nomination (and quite possibly the only one). In that sense he was the public face of British PR. A glance back at the press cuttings from before his arrest shows him variously described as a ‘PR mastermind,’ a ‘PR guru,’ a ‘PR mogul,’ and a ‘PR supremo.’”

The fact is that Clifford—who to the best of my knowledge did not represent a single FTSE 100 company—was somehow able to gain a more prominent place in the public consciousness than anyone from Weber Shandwick, Burson-Marsteller, Bell Pottinger or Blue Rubicon. And perhaps more to the point, a more prominent place than anyone from the Chartered Institute of Public Relations or the Public Relations Consultants Association.

To a certain extent his stature as a representative of our profession been enabled by the broader PR industry. He was featured prominently on PR Week’s “power list” for many years, and a few years ago was able to convince attendees at an “ethics debate” organized by the same publication that the PR industry has no obligation to tell the truth.

Even so, it is discouraging that someone from so far outside the PR mainstream, a man who was essentially a “press agent”—with the emphasis on the agent part of that equation, helping clients negotiate fees for their tabloid-worthy stories—could so easily become the public face of the PR business.

Clifford’s status speaks to a number of issues that the industry must address.

For one thing, we need to do a better job of explaining just what it is that public relations people do. This can be a challenge, given that there are as many definitions of PR as there are practitioners, but it should be possible to form a broad agreement on some core principles.

We could start by discussing the difference between PR and spin. PR—as the name suggests—is about building relationships; spin is essentially transactional, and in that regard is actually either (a) the opposite or PR or (b) the worst way to practice it.

And for another, we need more visible and proactive leadership from some of the genuine statesmen of our industry. It’s not just that Max Clifford was extremely visible; it’s also true that many real industry leaders—agency founders and CEO, senior clients—are more or less invisible. That creates a vacuum that disreputable figures are all too willing to fill.

The PR industry has a reputation problem that goes deeper than this one case. It needs to address it before the next big issue comes along.

.jpg)