Finsbury 21 Aug 2017 // 4:02PM GMT

---copy.jpg)

In 1962 the American economist Milton Friedman famously wrote, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.” Many large companies followed his lead. If they were ever asked to stake a political stand, there was only one answer: “Our sole priority is serving our customers.”

But today – when President Trump can

move a stock several percentage points with a single tweet, and when activist investors are more visible than

ever – companies know that “no comment” is not an option. Just look at the reactions

to Mr. Trump after the violence in Charlottesville, Virginia.

What’s more, leading executives

are finding that a public position on a political or social issue may not only

be necessary, it can be a positive for many reasons. But it only works if a company

plans carefully, formulates a smart communications strategy and follows

through.

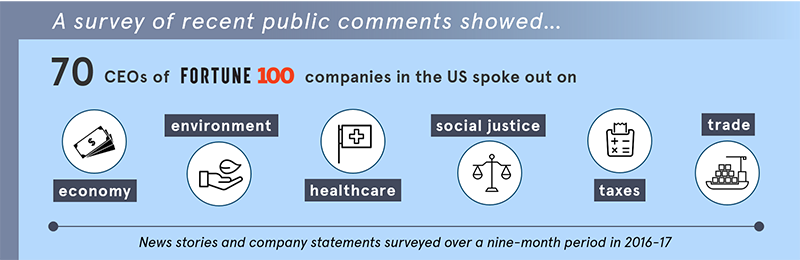

A team of my colleagues here at

Finsbury surveyed public comments by the CEOs of the Fortune 100 companies in

the United States over a nine-month period in 2016-17, and found that no fewer

than 70 had spoken out on the economy, the environment, healthcare, social

justice, taxes, trade, or other issues of national or global importance.

Moreover, the vast majority of them made it clear that they were speaking on

behalf of their companies, not as individuals.

That said, they were hardly

reckless when they braved political waters. Though none of the 100 CEOs

endorsed Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy (about a dozen publicly

supported Hillary Clinton), many said they would work with him after he won in

November and took office in January. If they took issue with Mr. Trump, they

did it diplomatically. Most of those who spoke on global trade, for instance,

were in favor of opening it up, but they were careful not to tangle with Mr.

Trump and his American-jobs-first stance.

Dennis Muilenburg of Boeing,

which imports about 30 percent of the parts for its planes, said early on that

his company was “very supportive” of Mr. Trump’s plans: “I think Mr. Trump’s

engagement with industry is going to help us grow manufacturing jobs in this

country.”

Gregory Hayes of United

Technologies: “Everybody knows that free trade is what drives growth in this

country.”

But it’s instructive to look at

cases – such as Mr. Trump’s response to Charlottesville, or the American

withdrawal from the Paris climate accord – in which executives said they felt

compelled to speak out in opposition. By going public on controversial issues,

they probably did their companies some favors, even if it may not have seemed

that way in the heat of the moment.

Kenneth Frazier, the chairman and

CEO of the pharmaceutical company Merck & Co., was one of 28 executives on

the president’s American Manufacturing Council. After Mr. Trump’s tepid first

response to the white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, Mr. Frazier said

he was leaving the council. “America’s leaders must honor our fundamental views

by clearly rejecting expressions of hatred, bigotry and group supremacy, which

run counter to the American ideal that all people are created equal,” he said

in a statement.

He and Merck said nothing more.

Within 16 hours, two other council members also left, and within two days, the

council and another on economic policy were disbanded. A fairly representative

statement came from Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan Chase: “I know times are tough for

many. The lack of economic growth and opportunity has led to deep and

understandable frustration among so many Americans. But fanning divisiveness is

not the answer.”

There was also this from Mary

Barra of General Motors: “Recent events require that we come together as a

country and reinforce values and ideals that united us — tolerance, inclusion

and diversity — and speak against those which divide us — racism, bigotry and

any politics based on ethnicity.”

Their statements were measured,

brief, easy to quote, and calming. Each company positioned itself as a voice of

reason at an upsetting time. And each probably helped itself by showing that it

was willing to stick to its values – something that surveys show is

increasingly important to consumers.

And there’s a lesson in there:

that a company that stands for something stands to gain – as long as it follows

some basic guidelines.

Pick your battles:

Are you speaking on an issue that is of importance to you? Are you sincere and

open about it? Are you putting your money where your mouth is?

Do your issues align with your

business? Tolerance and inclusiveness do for most major

companies, Merck included. A statement from Mr. Frazier, posted long before

Charlottesville, says employees’ “varied skills, experiences, backgrounds and

cultural perspectives help us better understand the needs of diverse customers,

healthcare providers and patients who ultimately use our products.” So the

decision to break with the White House was not a break with anything else Merck

stands for. Companies lose credibility if they take positions on issues that

have nothing to do with them; they gain credibility by standing their ground.

Know your audience. Who

will be affected if you take a controversial stand? Consumers? Employees?

Shareholders? Regulators? Make plans for how you will explain your rationale to

all of them. If it’s a struggle, maybe you’ve picked the wrong issue.

Be authentic. If a company picks an issue or a cause just because it looks good, it can look pretty bad. People will see right through it.

Ned Potter is a Senior Vice President in Finsbury's New York office

.jpg)