Arun Sudhaman 27 Jan 2015 // 8:55AM GMT

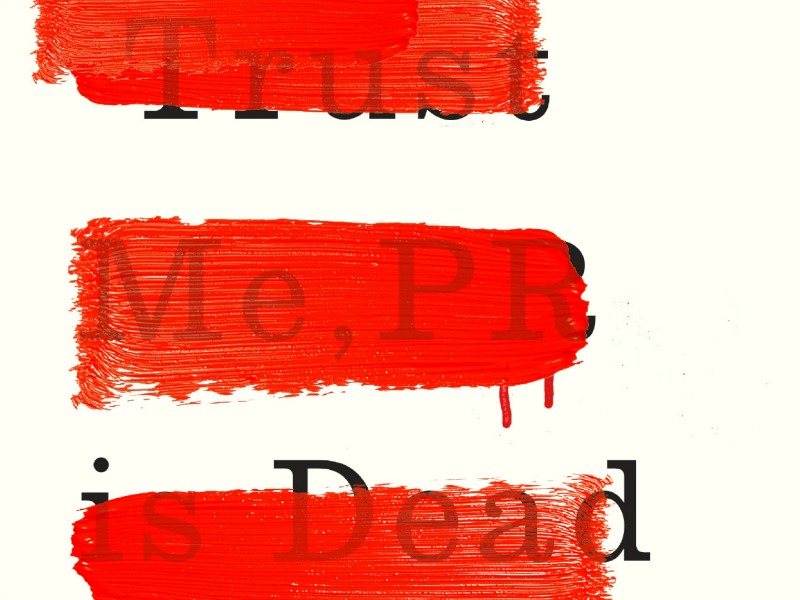

'Trust Me, PR is Dead'

By Robert Phillips (Unbound)

Robert Phillips is not the first person to attack the PR industry while running a consultancy of his own, but his effort might be the most thorough yet. After trolling the industry for the better part of a year with his claim that “PR is dead”, the former Edelman bigwig’s new book finally emerges, much anticipated by an industry that is justifiably wary of Phillips' motivations, given the dramatic nature of his exit from the world’s largest PR firm.

They need not worry too much. Phillips' prescription for PR’s ills do not so much break new ground as cohesively combine much of the disparate strands of thought about the discipline’s pressing need for reinvention, in a style that is, by turns, provocative and amusing. On some topics, such as corporate social responsibility, ‘conscious capitalism’ and the disruption of media and politics, he is positively illuminating, arguing persuasively for corporations and public leaders to eschew all of the spin and rhetoric in favour of simply behaving better.

In that sense, it is not a complex message, and certainly not one that will count as news within the PR industry. Yet, Phillips' desire to throw the baby out with the bathwater can be a little jarring. Not without justification, he argues that big PR networks are not necessarily best placed to evolve their models to reflect the tremendous changes in society. But he makes little mention of the many consultancies (including, presumably, his own) that are.

Instead, the PR industry, to hear Phillips tell it, is interested only in consumerism, manicured messages and making money. In particular, he pinpoints a lack of talent and an inability to get to grips with data. There is undoubted merit to these claims, but it overlooks the seismic changes that are taking place among more enlightened PR consultancies and people.

Indeed, it is difficult to square away some of his more controversial assertions with reality — the PR industry is "seemingly unaware of its own death throes"; "PR people...want us to believe in a manicured reality and forever happy endings." Ultimately, Phillips sometimes succumbs to the very trap he accuses the PR industry of — creating a straw man and then applying some highly effective spin to get his point across.

Clients, despite bankrolling all of these awful PR agencies, get off much easier, which could invite a measure of cynicism. This is unfortunate, because in a sea of mediocre public relations books, this one is very good and, often, very funny. Overlook the whiff of bitterness towards the agency world, and you will find a book that makes a strong and credible argument for a more sustainable compact between business, government and society. Trust me.

.jpg)

.tmb-135x100.jpg)

.tmb-135x100.jpg)