Paul Holmes 09 Feb 2017 // 8:10PM GMT

Another week, another example—another pair of examples, really—of the decisions facing large corporations in Trump’s America.

In one case, retail giant Nordstrom made a business decision, to stop carrying first daughter Ivanka Trump’s clothing line. The company was immediately attacked by the president on Twitter, and later by White House spokesman Sean Spicer, who described the decision as “a direct attack on [Trump’s] policies and [Ivanka’s] name.” Ultimately, and in clear violation of federal ethics laws, Kellyanne Conway urged consumers to "go buy Ivanka's stuff."

As has become the norm in such cases, neither Trump nor Spicer made any attempt to justify their claims that the move was politically-motivated. Their baseless attack was clearly an attempt to damage the Nordstrom brand and use the “bully pulpit” of the presidency to help the Trump family make more money.

It was the very definition of corruption and kleptocracy.

The only good news—and this should send a message to other businesses—is that it failed in its obvious objective. The company’s share price dipped slightly at first—like Boeing and Lockheed Martin before it—but rebounded almost immediately, and ended the day (a day when the market as a whole was flat) up 4%.

That’s what makes the week’s other notable story of corporate-political interaction the more alarming of the two.

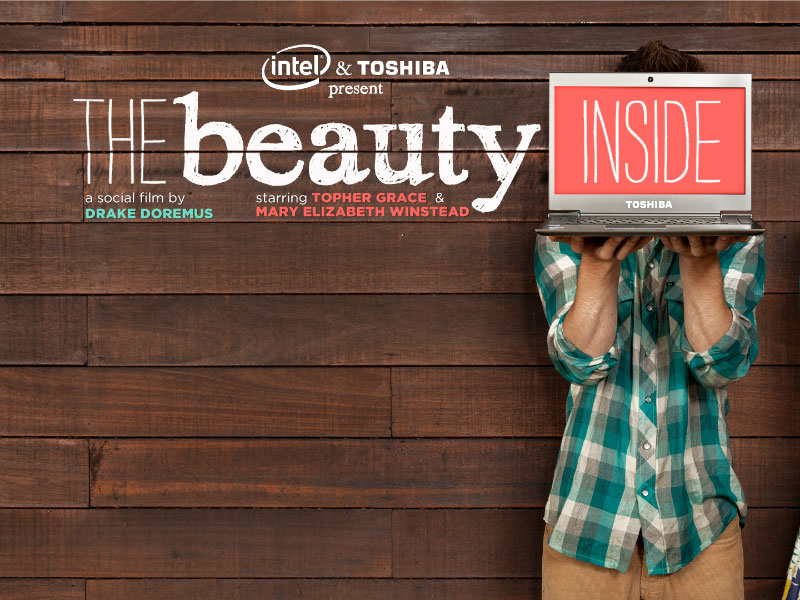

This one involved Intel, whose CEO Brian Krzanich met with Trump in the Oval Office, and announced plans to invest $7 billion in Arizona, creating 10,000 jobs and making what Krzanich said would be “the most powerful chips on the planet.”

The meeting was clearly a win-win. Intel received a uniquely powerful platform for its new product announcement, generating much more attention than the launch of a slightly better chip would normally receive. Trump, meanwhile, got to take credit for another infinitesimally small but high-profile jobs story.

(Whether the jobs created are “new” or in any way tied to the new administration is arguable at the very least. “This would have happened anyway; this was always part of their plan,” one analyst told the Washington Post.)

At least one (unidentified) PR executive—quoted in the Financial Times this week—seems to think this is a smart strategy. Discussing a similar decision by GM last month, he said: “They repackaged old news… There is nothing wrong with that and Trump thanked them for it.”

So let’s be clear: if Intel had made such an explicit quid-pro-quo with any other regime, in Africa or the Middle East—providing dishonest propaganda points for the regime in exchange for product endorsement—we would have no hesitation in labeling such a deal corrupt. (Of course, it should come as no surprise that Trump has called the laws against foreign corruption "horrible laws" that put honest companies at a "huge disadvantage.")

Since this is America, let’s be a little more generous and say that some companies are willing to cut—this is the most generous way to put it—sleazy deals with the new president for short-term commercial gain. Whether that’s a smart long-term strategy remains to be seen.

.jpg)